For the last couple decades social scientists and economists have been asking similar questions but from two different angles. They have wondered why it is becoming increasingly rare to see Americans lift themselves out of poverty.

We saw the American Dream come true pretty consistently back in 1940. Back then a son or daughter had a 90% chance of earning more than their parents did. Now that chance has dropped to just 50% (Raj Chetty’s American Dream, The Atlantic). Our children have just as much chance to earn less than their parents as they are to earn more.

What is happening? And can we reverse the trend? Is there anything we as a society can do to support the American Dream and help to make intergenerational income growth more common? Scientists are incredibly close to identifying the real reasons behind upward mobility, and it could transform the way we help families facing structural challenges.

The Problem isn’t Race or Class. It’s More Obvious that That.

Any bill with bipartisan support is a huge standout in our polarized political climate. And it was with bipartisan support that President Donald Trump signed a bill in February providing national support to a relatively under-the-radar housing program. The aim of the program is simple: It wants to help guide recipients of Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) support to make better educated choices about where they use their vouchers to purchase a house.

Why is this transformational? Driving the program is the groundbreaking analysis of Harvard economist Raj Chetty. The data that HUD recipients will use builds on the insights of Chetty and his team of researchers, and it will place families into locations that have a proven track record of upward mobility. If the trend continues as it has for decades, the kids of these families will be much more likely to earn more than their parents.

Chetty’s team received bipartisan support because their case is extremely compelling. They aggregated newly available sources of national data to analyze generational patterns of mobility and stagnation. One of their largest discoveries was something that we know as individuals but couldn’t see as a country. His team found that location is highly influential on a child’s prospects in life.

Some areas of the United States are just as supportive of upward mobility as our country was as a whole decades ago. These places see children from families in the bottom quarter of wage earners often earn more than their parents, sometimes quite a lot more. However, in other areas the opposite happens: Kids from low socioeconomic status backgrounds very rarely become affluent, no matter how talented they are. In these locations, the American Dream is almost a fantasy.

It might seem obvious that location is important. We all know why a 1-bedroom in San Francisco costs $1 million while you can buy 4 acres of waterfront property in Gaston, North Carolina for $86,000. But the opportunity map can be counterintuitive. Many locations you’d expect to be supportive, aren’t, and vice versa.

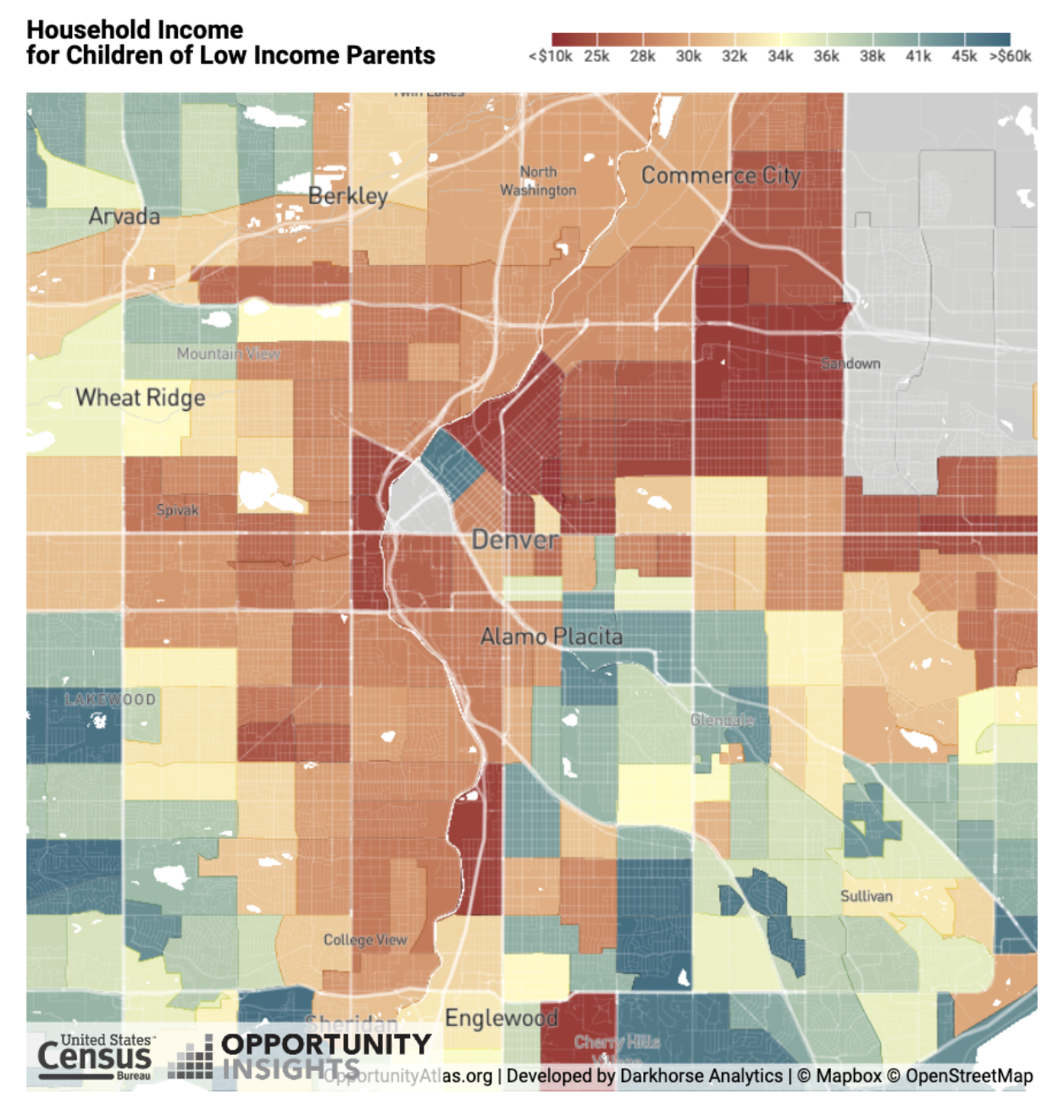

The geophysical distance between these locations can be quite small; we are talking blocks or a few miles apart. But you can look for yourself.

Blue-green areas are neighborhoods where kids have a better shot of rising out of poverty. Red areas are where most kids who are born into poverty continue to live in poverty. This data is available to anyone via Opportunity Atlas.

It isn’t quite what you expected, is it? The opportunity map doesn’t strictly adhere to class lines, or racial lines, or even the best public schools. Right now there is no premium placed on mobility because no one knows where to find it! That’s what makes Chetty’s discoveries valuable. They can point us toward small changes that could result in significantly different outcomes for the next generation.

The Distance between Social Ties and Good Decisions

If successful the pilot program in the $28 million bill could be expanded to all 2.2 million families who receive HUD help every year. But even if/when that happens, we cannot expect to solve all our problems by moving families. We need to figure out what makes some communities more supportive than others so we can recreate the positive traits in areas of need.

You might think that resources and wealth would create opportunity, but this is not necessarily true for everyone. Ironically, analyses have found no correlation whatsoever between mobility and wage growth, employment, or other traditional economic indicators.

Social indicators are much stronger supports, characteristics like many two-parent families, low levels of income inequality, and little residential segregation. Good schools are also a factor but also not as influential as you might think. The community makes the difference.

It makes sense if you can lay judgment aside for a second. When children grow up in a space where people feel connected to each other and to them, they are more likely to connect in meaningful ways to society, living up to their potential.

At Minds Matter we see this principle at work every day, as our mentors help bring that sense of college-readiness perspective and community to kids who might not have had that access otherwise. These relationships serve as the bedrock for stronger choices and more opportunity in their lives. Knowing we play a small part of the communal forces shaping the prospects of the next generation inspires me, and it gives me hope that we can act on the local level to make our communities a bit brighter for the next generation.

Photo Credit: Skitterphoto from Pexels