The recent college admissions scandal in which wealthy parents of students allegedly bribed and manipulated the admissions system for their children has served as a stark reminder to many people that our educational system can be stacked against children who don’t come from privileged backgrounds. Fortunately, our justice system is working to ensure that the college admissions process is fair. And in many ways, it is at least trying to be. Kids are graded on the same scale whether they come from high or low-income households. But for kids from historically disenfranchised families, the intensive admissions process — as daunting as it is — may not be the most challenging barrier. In many ways, higher education systems are just not designed to identify, accept, or support them.

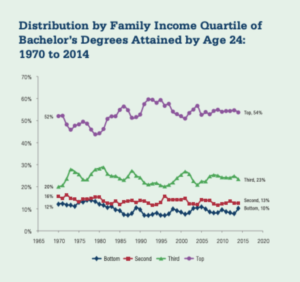

It is well-known that the majority of college graduates come from affluent families. In general college attainment decreases as family income decreases. The chart below breaks down the economic composition of kids who graduate by age 24. Each color represents a quintile of college graduates (that is, 20% chunks of the population).

Cahalan, Margaret, et al. “Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States: 2018 Historical Trend Report.” Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education (2018).

In an ideal world, all five lines would be right at 20% — that is, students from all levels of income have the same proportion of degrees attained. But as you can see, top earners are represented at higher rates than other groups — 4-5 times as likely as those from the lowest-earning families who send the fewest kids to college.

When collegiates walk on graduation day, over half of them come from families in the top 20% of earners.

Since college graduates generally earn more income, demographic data show that higher education is at best reinforcing and at worst intensifying, socioeconomic stratification. It is important to understand why more affluent kids graduate from college than poor kids. Then we can identify ways to balance out the scales and give more kids a real shot at the American Dream — irrespective of their family’s income level.

How and when do students from lower-income families drop off the college path? Studies in recent years have begun to unearth some surprising answers to these questions along with interventions the system can take to even the odds.

“Summer Melt:” The drop-off between high school graduation and college enrollment

- For every 6 kids [accepted to college] from families in the top 20% of earners [who enroll], there is 1 kid who does not enroll in college.

- For every 6 kids [accepted to college] from families in the bottom 20% who enroll, there are 3 who do not.*

*The National Center for Education Statistics, 2016

There is no one cause for the discrepancy in graduation rates. The cumulative effect results from a series of small barriers throughout the college experience, and each one proves progressively more impassable to those from lower income families. These barriers add up over time leading to very few low-income students achieving college graduation. Think about it as a series of false summits on a steep mountain peak for kids from low-income families, versus a clearly marked and paved trail on a much more gradual incline for those from higher-income backgrounds. The system isn’t designed to look out for these lower income kids because it assumes students have more knowledge and experience dealing with institutions than they actually do.

The Colorado Department of Education reported that 80% of the class of 2018 graduated in 4 years or less. That’s the average for all kids. The graduation rate for lower income kids was 73.3%, only 7% less than the average. Let’s assume that’s a rub, for all intents and purposes.

When you compare this to college graduation, the ratio shifts to nearly 5 graduates for every 1 from a low-income background. How did we get here?

Enrollment is the first challenge. Many high school grads earn acceptance to college. But when summer turns to fall, about a fifth of them won’t enroll (Castleman and Page, “A Trickle or a Torrent? Understanding the Extent of Summer ‘Melt’”). These are kids who have gone through all the steps: they have graduated high school, completed college applications, and been accepted. They’ve done all the hard work, but for one reason or another, they don’t go. What could these reasons possibly be?

Researchers have posited any number of reasons for summer melt. Maybe some kids decide they just don’t want to go. Maybe others still realize they no longer can afford it or find funding.

Those are all valid reasons. But two researchers discovered that a lack of guidance and consistent support in the months leading up to the first day of college can be among one of the largest problems.

A Simple Intervention Can Even the Odds of Enrollment

Many students have parents who are able to streamline the enrollment process. Affluent parents often shoulder much of the administration behind enrollment since in many cases they have done it before, or they can hire support to help. They know what to do, and they have the financial and other resources to handle the obstacles.

Low-income parents cannot always offer the same luxury. According to the National Center for Children in Poverty, fewer than four out of every 10 (39%) low-income kids have a parent who finished at least some college. They may have no one to provide guidance or even assurance that they are on the right path.

Castleman and Page, two researchers who had looked into summer melt, thought that not having a guide who has been through the process before could be the most significant problem. To test this, they had counselors reach out to a group of randomly selected college-bound students during the summer. Then, they compared this intervention group with a control group who received no outreach.

This simple intervention resulted in a 12% increase in immediate enrollment! Without intervention, 76% matriculated. Of those who received the outreach 88% showed up at school (Castleman and Page, “College Counseling to Mitigate Summer Melt”). That is a huge difference — nearly half the gap, with just a simple relationship. Schools across the country are already exploring various ways to apply these findings to their freshman enrollment practices.

Hope for greater equity in education

Summer melt is only one small part of the systemic obstacles that children from low-income families face in graduating college, but even small changes in the educational process can help shrink the gap in graduation rates for economically disadvantaged kids.

School isn’t for everyone, and we don’t expect everyone to get a degree. College is just one of many options. If a student has a full-ride to Harvard and then decides to run their mom’s cleaning company, then go do it! That said for us at Minds Matter the most important thing is having the options to make decisions about your life that you deserve based on your drive, determination, and aptitude. Too many of our kids don’t have those options by no fault of their own, so our college graduate Mentors — folks who have been through the process before — aim to change that.

We might not see perfectly ideal demographics for college graduates for a while. We’re working to change that, but we accept it in the short run. But if schools start to conduct outreach to their incoming freshmen, or if Mentors the students have worked with throughout high school like those at Minds Matter can provide ongoing support, the system will be a bit fairer for everyone.